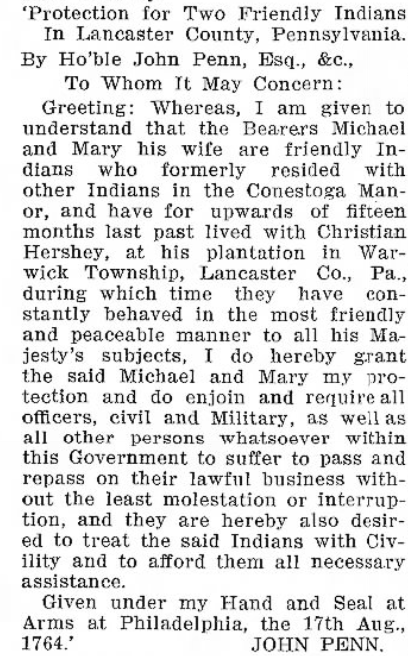

From the very beginning of the alleged end of our people, there were issues with the statement that the Conestoga-Susquehannock were extinct. The Paxton boys murdered 20 Conestoga, leaving two unaccounted for. This mystery would not be solved until some time later. Before the attack on Conestoga town, a Conestoga-Susquehannock couple named Michael and Mary had moved to work on the farm of Christian and Anna Hershey (relatives of Hershey Chocolate founder Milton Hershey). When the Paxton boys came looking for the couple at the Hershey house, Christian and Anna hid them in their cellar. This couple remained with the Hershey family until their deaths, and were buried on the property. This is confirmed in a letter from John Penn, who specifically called for the protection of these last two survivors. You can still visit their grave marker on the old Hershey property, which is now Kreider farms. This not only commemorates the Quaker values of their family, but also refutes the narrative that the Conestoga-Susquehannock were extinct in 1763.

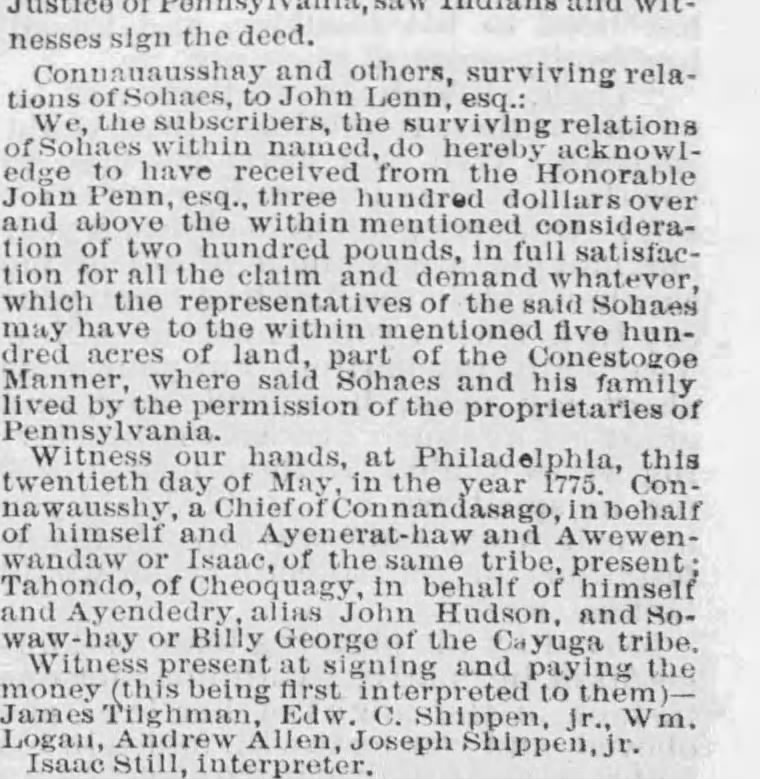

In 1768, concerns among the Penn family that Conestoga survivors may claim the land at Manor township were sufficiently great to convene a treaty with the Haudenosaunee in an attempt to clear any potential Indigenous claims to that land. The language of this treaty is available in the gallery below, but explicitly lists “dependent” tribes, such as the Conestoga-Susquehannock, as being among those who were no longer entitled to any land claims in the area. This specific language implies that there was some awareness that there remained stakeholders among the Haudenosaunee who might be able to claim their treaty rights. This was further explored in a 1775 agreement which confirmed “surviving relations” of “Sohaes” (also known as Sheehays) were living among the Haudenosaunee. The prospect of our community having the ability to reclaim the land at Manor township was so concerning that the Penn family paid these surviving relations $300 for the remaining 500 acres over a decade after the colony of Pennsylvania declared our people extinct. Why would the Penn family take such specific measures to protect their title to the Conestoga land if there were truly no remaining Conestoga-Susquehannock people?

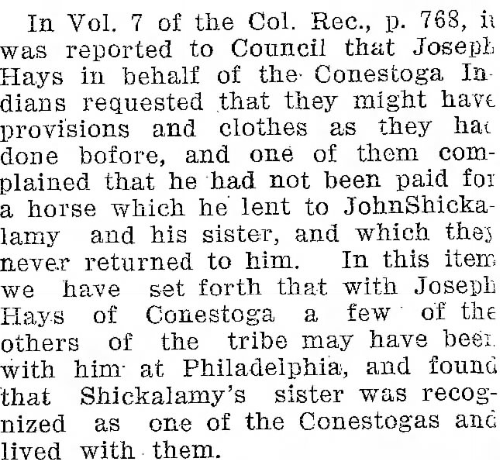

The 1775 claimants were largely among the Cayuga, which is significant, as the Cayuga are connected to the Conestoga through Oneida Chief Shikellamy, who married a Cayuga woman. His children were all considered Cayuga people, as the Haudenosaunee tribes practice matrilinear descent. Notably, some historians argue that Shikellamy himself may have been Susquehannock. While this has not been proven yet, and kinship relations among Haundenosaunee tribes are more complex than in colonial societies, there is some evidence to suggest that this may have been the case. In a 1757 deposition Shikellamy’s sister was recorded as a Conestoga Indian implying that one or both of their parents were Conestoga people. This connects the relationship between the Cayuga and the Conestoga, and explains why the aforementioned land claims were settled with people identifying themselves as Cayuga. Their relationship to Sohaes has not yet been determined, though kinship between all three tribes was and remains strong. While research into his sister is ongoing, it is believed that she was the ancestor of the 1845 land claimants.

Gallery:

While these attempts to clear title for that land were very specific, they fail to address the land sold by the Penn family prior to the massacre. The original tract set aside for our ancestors was 16,000 acres, but from 1701-1763 the Penn family sold parcels of that land without addressing the treaty commitments, reducing our established territory down to a mere 500 acres by the time of the massacre. However, further efforts to reclaim the land or address this issue were disrupted by the revolutionary war, which uprooted the entire region just 13 years after the massacre, and just a year following the 1775 treaty distracting any and all efforts as the whole region was thrust into conflict. The revolutionary war nearly tore the Haudenosaunee alliance apart and disrupted the conversational kinship required to prove claims to that land and galvanize the Conestoga Susquehannock survivors as an independent tribe. The Oneida people, among whom lived the majority of Conestoga-Susquehannock survivors, would side with the fledging United States of America, alongside the Tuscarora. Every other Haudenosaunee tribe, including the descendants living among the Cayuga, sided with the British. This devastated the Haudenosaunee community, and turned brother against brother in a brutal fight for US independence.

Notably, Chief John Skenandoah, who lead the Oneida to support the United States, was Conestoga-Susquehannock in ancestry. According to the Oneida Indian Nation, Skenandoah was adopted into the wolf clan of the Oneida from the Conestoga community. It was for this reason that he was unable to be a hereditary chief in the Oneida nation. Nonetheless, he rose to prominence through exceptional leadership and foresight and became one of the most impactful leaders in Native American history. Some of his estimated 10,000 descendants are enrolled among the Conestoga Susquehannock to this day, proving beyond any doubt that there are people today who can trace their ancestry to the Conestoga Susquehannock people.

A letter from John Penn, confirming the survival of two Conestoga residents, Michael and Mary, who were kept safe by the Hershey family.

An excerpt from the 1768 treaty, which specifically mentions dependent tribes, their children and relations as being unable to claim the land at Conestoga.

Early colonial records confirm the many routes of kinship between the Oneida and the Conestoga. Famous Oneida chief Shikellamy had a sister who was a Conestoga Indian. This report was written in 1757, just six years before the massacre, and confirms that there were Conestoga that may have been living in Philadelphia at that time. It is not clear that these Conestoga were present for the 1763 massacre.

The 1775 treaty to the relations of Sohaes among the Cayuga. The Cayuga have connections to the Conestoga through Oneida Chief Shikellamy, whose sister was recorded as a Conestoga, and whose children are recorded as Cayuga.

The grave of Michael and Mary, located on what is now the Kreider farm near Lancaster Pennsylvania.